George, a young Ugandan man, is leading a relatively normal life in Kampala working as an IT specialist.

Then COVID hits and his work disappears.

Scam Factories

The inside story of Southeast Asia’s fraud compounds

Like many Africans, George hopes to change his fortunes in Dubai. (George isn't his real name as he's worried about his safety.)

But life is difficult and after two years, he is still struggling to make ends meet.

In August 2022, a friend points him to a well-paid job in Laos. It's a six-month contract offering US$1,500 per month, plus commissions and free accommodation. Everything seems to check out.

George is soon on his way to the Golden Triangle, a lawless area on Laos’ border with Myanmar and Thailand.

He's given a contract completely different from what he was promised in Dubai. He's asked to pay his new employer the equivalent of US$2,200.

His bosses confiscate his passport and phone and he realises he is trapped.

For two months, George drags his feet and refuses to do any scams, insisting he is just an IT guy. Then, one day, he is sold to a second scam company in Myanmar, just across the Mekong River.

A booming industry

George is typical of thousands of victims working in the scam industry in Southeast Asia. In the last 30 years, the industry has gone global, raking in billions of dollars every year.

Exactly how much is hard to quantify. The UN estimates victims in East and Southeast Asia lost anywhere from US$18–37 billion in 2023. That same year, Americans are estimated to have lost more than US$10 billion to scammers.

The online scam industry got its start in Asia in the 1990s, first in Taiwan, then spreading to China. When authorities in both countries began targeting these schemes, scammers started looking for new bases for their operations.

In the 2010s, they began springing up across Cambodia, the Philippines, Myanmar and Laos, lured by lax regulation and local elites willing to turn a blind eye – and actively support and benefit from the industry.

Because the scam compounds also needed high speed internet and office space, they were often set up alongside casinos or online gambling operations.

So far, we've identified more than 300 scamming sites across Cambodia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Laos. There are likely to be many more.

In Cambodia's once-quiet coastal city of Sihanoukville, the gambling industry started taking off in 2017.

By 2019, glitzy, high-end hotels and condos – and plenty of unfinished construction projects – dominated the skyline, and gambling was generating billions a year for the local economy.

Scam Factories is a special multimedia and podcast series by The Conversation. Listen to the podcast series here.

The boom was short-lived. The Cambodian government cracked down on online gambling that year and many of these operators were shut down, leaving the scammers to take advantage of the deserted facilities. Laid-off workers from the casinos and online gambling operations also migrated into the scamming industry – or were just kidnapped off the streets.

A similar scenario played out in the Philippines after new regulations for the licensing of online gambling operations were adopted in 2016. Within a few years, many of these newly licensed operations had become fronts for the scam industry, leading to a decision last year to ban them.

It's a different story in Myanmar. Gambling was long outlawed here, but some casinos did start to emerge decades ago in the areas on the Chinese and Thai borders controlled by armed ethnic groups. These areas became hubs for myriad criminal operations, including the scamming industry.

The industry then boomed in these border areas when civil war broke out following the 2021 military coup.

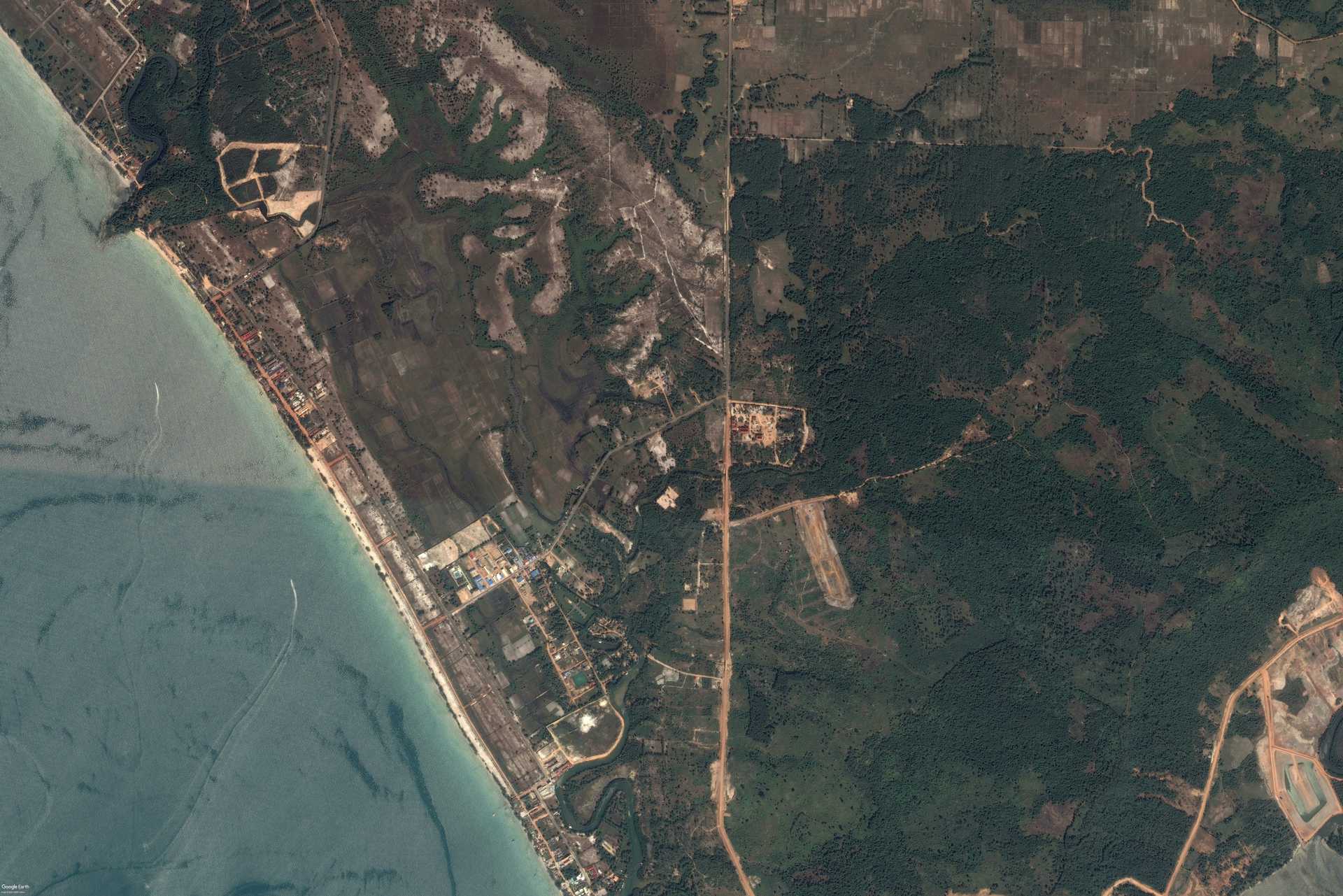

In late 2019, this area by the Moei River is empty agricultural land.

Soon after, construction begins.

In just a few years, it will become one of Myanmar’s most notorious scam compounds.

Currently KK Park and its surrounds cover about 7.5 square kilometres.

This month, a militia group allied with the Myanmar junta launched a massive crackdown on compounds along the Myanmar-Thailand border, leading to the release of around 7,000 people. Thai authorities have also cut the internet, fuel and electricity supplies to the border areas where the scammers have operated with impunity.

Sophisticated operations, shadowy figures

In recent years, the scam industry has become increasingly professional. These operations have built bigger compounds, with offices, dormitories, shops, entertainment venues and other amenities for workers. Many have clubs similar to brothels, where young women provide sexual services to managers and scammers as a reward for good performances.

Their operations have become more like "proper" companies, as well, with departments overseeing human resources, logistics and IT.

Head of Department

Monitor overall activities

Core Managers

Manage team leaders, teach scam techniques, and track important scam targets

Team Leaders

Discipline new scammers, teach basic scam techniques, track scam targets

Scammers

Screen scam targets on social media, establish relationship with scam targets

1 person

11 people

38 people

244 people

It is often challenging to identify who is at the top of the hierarchy, but it's clear that organised crime groups are involved. Scam compounds are also linked to local politicians and power brokers through murky networks of interconnected companies and entities. This acts as a protective umbrella for the compounds.

We've found these links in corporate documents for the public-facing real estate or gambling operations where the compounds are located. In some cases, companies linked to scam sites have been registered at the addresses of powerful local figures. In others, their relatives or associates of prominent figures are listed as directors.

Social media posts also provide evidence of these links. We've seen posts of scam compounds gifting patrol cars to police in Cambodia. Others show government officials, business leaders and other elites at ribbon-cutting ceremonies for developments where compounds are later found to be operating.

There's a wealth of evidence that, at the very least, officials know about these operations and in some cases are directly involved.

In Cambodia, authorities have swung between denying there is a problem to staging periodic crackdowns. But the industry remains protected. One police officer told a local news agency in 2022: "These places don’t allow us to go in"

Many times, compound managers also have a direct line of communication with the police. When we were in Sihanoukville in 2022, the government launched a crackdown on the industry. We saw firsthand how quickly the compounds were evacuated. They had clearly been tipped off.

Within months, many of the scam centres were back in business, recruiting more unsuspecting people like George with false promises and brutal tactics.

In part three of our series, we describe how people escape scam compounds and the difficulties they face proving they are actually victims.